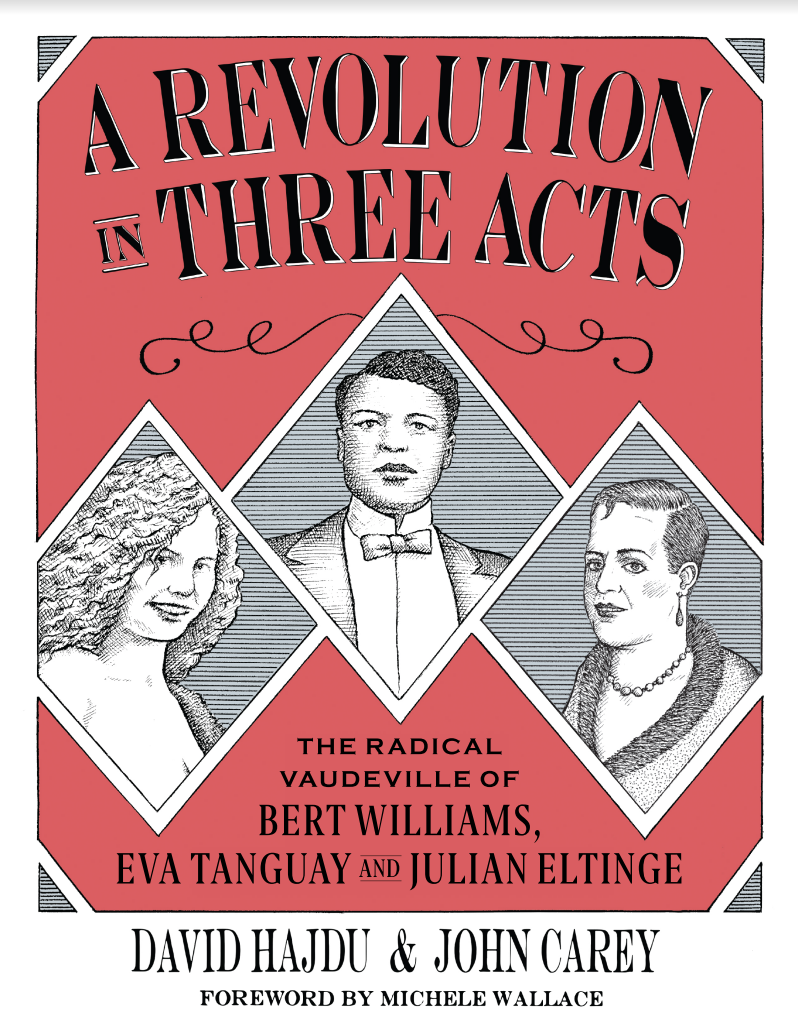

A Revolution in Three Acts

Bert Williams—a Black man forced to perform in blackface who challenged the stereotypes of minstrelsy.

Eva Tanguay—an entertainer with the signature song “I Don’t Care” who flouted the rules of propriety to redefine womanhood for the modern age.

Julian Eltinge—a female impersonator who entranced and unnerved audiences by embodying the feminine ideal Tanguay rejected. At the turn of the twentieth century, they became three of the most provocative and popular performers in vaudeville, the form in which American mass entertainment first took shape.

A Revolution in Three Acts explores how these vaudeville stars defied the standards of their time to change how their audiences thought about what it meant to be American, to be Black, to be a woman or a man. The writer David Hajdu and the artist John Carey collaborate in this work of graphic nonfiction, crafting powerful portrayals of Williams, Tanguay, and Eltinge to show how they transformed American culture. Hand-drawn images give vivid visual form to the lives and work of the book’s subjects and their world.

This book is at once a deft telling of three intricately entwined stories, a lush evocation of a performance milieu with unabashed entertainment value, and an eye-opening account of a key moment in American cultural history with striking parallels to present-day questions of race, gender, and sexual identity.

(This text courtesy of Columbia University Press)

Excerpt:

Coming Soon.

Reviews:

A welcome graphic celebration of the work of three important vaudeville artists.

Neither revolution nor radical are terms commonly associated with vaudeville. Yet Hajdu and Carey effectively illuminate the significance of three trailblazers who merit such rhetoric and who have been largely forgotten since vaudeville lost its audience to the movies. The best-known among them is Bert Williams (1874-1922), a Black entertainer who performed in blackface along with his longtime partner, George Walker, and who earned international renown for their “broad ‘coon’ humor.” Beneath the blackface, the Bahamian-born Williams was playing a role that was at odds with his intelligence and articulation, with a regional accent he had to learn. After Walker’s death, Williams was recruited to join the all-White Ziegfeld Follies, where he never felt like he fit in. Few comedians of the era were more talented or popular, but the racial barriers were often too much for him to overcome. As a White observer noted, “he was the funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew.” While Williams both challenged and struggled with racial stereotypes, Hajdu and Carey celebrate two entertainers who anticipated what would later be known as “gender fluidity.” Julian Eltinge (1881-1941) became a huge hit as a female impersonator, even as he projected a hypermasculine image offstage. His success helped inspire what was called the “Pansy Craze,” an “emerging phenomenon of drag performance.” Eva Tanguay (1878-1947) represented the sexually liberated “new woman,” and she “got away with promoting radical ideas by projecting a comical ‘kooky’ persona.” She was as wild as Eltinge’s depiction of femininity was refined, though their destinies were briefly entwined as they were engaged to be married. Though the title suggests a tripart structure, with capsule biographies of each artist, the narrative is characterized by jump-cuts and crisscrosses. Hajdu’s lively scholarship and critical perspective match Carey’s spirited renderings, which range from ebullience to devastation.

A sharp account that brings life and light to a period that has gone dark in popular memory. -Kirkus Reviews

Music critic Hajdu (Adrianne Geffel: A Fiction) and artist Carey recapture the bygone days of vaudeville, bringing to fresh light and life the stories of three transgressive performers in this entertaining graphic group biography. Hajdu convincingly argues that, through their individual acts, these performers “transformed themselves for the vaudeville stage and their audience was transformed in the process.” Bert Williams (1874–1922) subverted the virulent racism of the early 20th century by performing his own version of minstrel shows, determined to present his authentic Black experience to white audiences. Eva Tanguay (1878–1947) performed uninhibitedly sexual musical numbers, while her fierce rejection of “acceptable” behavior for women anticipated modern-day feminism. Rounding out the trio, the closeted Julian Eltinge (1881–1941) devised meticulous cross-dressing presentations, which mainstreamed expressions of gender fluidity (he once advertised himself as a “feminine delineator”). Though all three met with great success, the advent of motion pictures eventually killed off vaudeville and their careers. Carey’s art can be stiff, but his hand-drawn, crosshatched style ably captures the flavor of the post-Victorian era. The history is relayed via robust storytelling, combining a little-remembered piece of showbiz history with insights into the ways in which entertainment both reflects and shapes American cultural life and values. - Publishers Weekly

The graphic history A Revolution in Three Acts profiles the careers of three daring and influential vaudeville entertainers, from their ambitious beginnings to their tragic ends.

Bert Williams was a singer, actor, and comedian who chafed at the limited opportunities for Black entertainers and worked to present images other than blackface minstrel-style shows. Eva Tanguay developed a following with her independence from traditional women’s roles, and Julian Eltinge was known for his convincing impersonations of women. All three pushed the limits of social acceptance to become icons of the vaudeville stage. The book follows them as they gain fame and fortune, their fates sometimes linked by common associations or even a shared stage. But all three are also undone by difficult transitions to the age of film, and suffer desperate or premature ends.

The book’s composition is masterful, weaving the three stories into a cohesive, captivating tale of a bygone era, at turns holding out examples of the similarities or differences in their lives. The art’s detailed, cross-hatched style, which is aided by extensive visual and textual research, captures Tanguay’s outlandish costumes, Eltinge’s transformational performances, and even scenes from the silent film shorts of Williams, his sly facial expressions changing panel by panel.

The larger impact that Williams, Tanguay, and Eltinge had on American entertainment is evident today: a legacy of challenging assumptions and preconceptions about race, gender, and sexual identity. A Revolution in Three Acts is an incredible work of historical scholarship, entertainment, and artistry. -Peter Dabbene, Foreword Reviews

“A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay and Julian Eltinge” by David Hajdu and John Carey is the surprise of the year for me because there’s so much I didn’t know or suspect about early 20th-century mass entertainment and its impact on how America saw itself.

These three iconic performers — the Black star of minstrel shows, the female performer who rejects her gender and the male who identifies as female — navigate vaudeville during the twilight of the Victorian age trying to find their place in society. The results of their artistic pursuits are tragic, comic and always poignant. - Tony Norman, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

This is an extremely remarkable comic, at once a historical look at the great and hugely popular genre of vaudeville, and a treatment of the margins, racial and gender, that pushed closer to the surface than radio or films would reach before the 1950s. David Hajdu is a distinguished music critic and a professor at Columbia University. His artistic collaborator, John Carey, less well known, worked at Greater Media Newspapers for decades. Neither has produced a comic until now, but Hajdu wrote an insightful history of comics entitled The Ten Cent Plague, more than touching upon the condemned but lively elements of popular culture.

Bert Williams, “the son of laughter” in contemporary advertising of Vaudeville, was almost certainly the first native of the little island of Antigua, then still in the British West Indies, to make himself a major star in the US. He sang, danced, told jokes, charmed (white) audiences far and wide, and became himself a producer of shows starring himself. He exhausted himself and died young, just as he reached his apex of success.

Eva Tanguay is remembered for one phrase, “I Don’t Care!” hailed by Andre Breton and the surrealists as capturing the spirit and radical possibilities embedded within popular culture. Flagrantly transgressive, she challenged every limitation of the lingering Victorian culture, dressing outlandishly, for instance, wearing pennies glued to a revealing body suit at the moment when the Lincoln Penny was introduced and fleeing when the police arrived to arrest her. She joined Williams on stage and drove audiences wild.

Cross-dressing Julian Eltinge completes this narrative. By way of Harvard and Hasty Pudding, he starred as a female performer, singing and dancing up a storm. Holding nothing back, he openly proclaimed his sexual passion for a black man (doublng the provocation), with himsef as “The Sambo Girl,” on stage and in the sheet music of the day. The very idea that Eltinge could publish a magazine under his own name offers a transgressive moment in time and in the rising pulp magazine craze.

The genius of the comic intertwines the stories, sharing the threats of the cops and other thuggish males. Tanguay and Williams were widely rumored to be lovers, but the rumor that she was to marry Eltinge inspired no limit of mean-spirited satire (“who will wear the breeches?”) and some good spirited as well. But movies, even without the severe restrictions to come later, were just too limited for this leap out of propriety. (Bert Williams was also in several film shorts, but these are lost.)

The art of Revolution in Three Acts finds John Carey perfectly suited with a greyish, sketch-like style, offering a kind of fluidity suitable to the subject. He aspires neither to realism, in the ordinary sense, nor to the altogether imaginative comic-art style adopted or adapted in modern “art” comics. Rather, it is his own.

The high spirits of these three characters, the visions they had of themselves and the crushing reality of a world unsuited for them, comes home collectively as we follow their lives. Eltinge, an entrepreneur in his own mind, bought a large chunk of land in California’s Imperial Valley, with a vision of a resort and a theatrical complex. He was quickly overextended, when a film showed his female impersonation at a disadvantge: society was not ready, although in failure, he inspired other stage female impersonators across the US and Europe. Tanguay, perhaps the luckiest, had a series of prominent affairs, passing before she could complete a tell-all memoir. - Paul Buhle, Comics Grinder