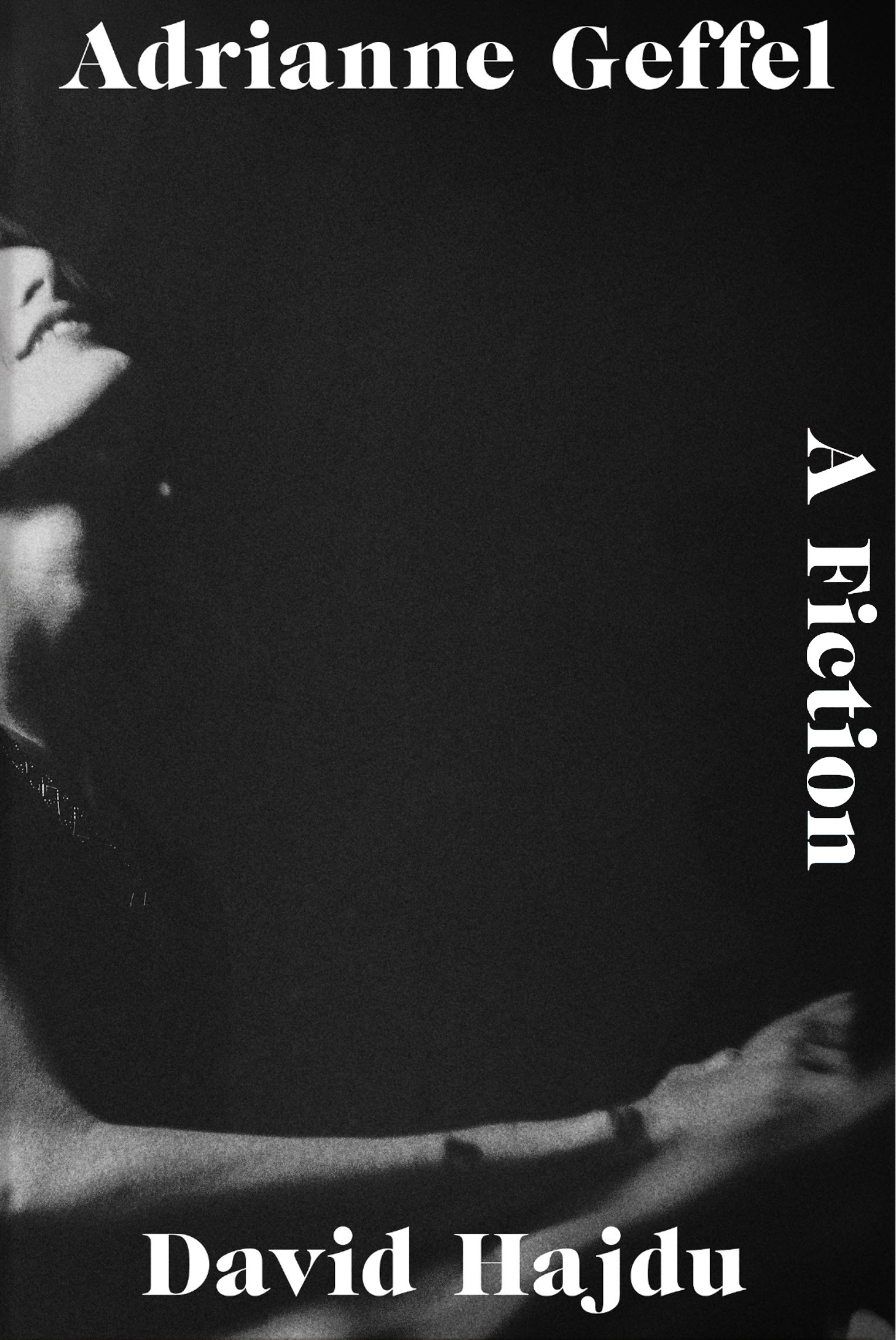

Adrianne Geffel: A Fiction

A poignant and hilarious oral history of a (fictitious) musical phenomenon.

Celebrated music critic and cultural historian David Hajdu unravels the mystery of a one-of-a-kind artist, a pianist with a rare neurological condition that enables her to make music that is nothing less than pure, unmediated emotional expression. Her name is Adrianne Geffel, praised as the “Geyser of Grand Street” and the “Queen of Bleak Chic.” Yet despite her renown, she curiously vanished from public life, and her whereabouts remain a mystery to this day.

Hajdu pieces together her story through the memories of those who knew her, inspired her, and exploited her―her mother, father, best friend, producer, critics, teachers―in this slyly entertaining work of fiction. Adrianne Geffel is at once a piercing satire, a vividly twisted evocation of New York in the 1970s and 80s, and a strangely moving portrait of a group of characters both utterly familiar and like none we’ve ever encountered.

(This text courtesy of W.W. Norton.)

Excerpt:

Sandor Kalman (former chief curator, K. Lewitt Gallery):

I knew Adrianne Geffel very well, of course. I discovered her. This is well known. I discovered many of the artists and also the musicians. Richard Prince, I discovered. Chuck Close, Steve Reich, Richard Serra—they were workers in a moving company when I discovered them. They had a truck. They carried boxes and furniture—whatever you needed moved, they moved it. That’s what they did. No one knew they were artistic. Chuck Close, an artist? Steve Reich, a musician? They were movers, and then I discovered them. They moved all the furnishings from our original location on 135 Crosby Street to our much better space at 82 Spring Street. They did very good work for me for a very nice price, and I recommended them to everyone. Before that, no one ever heard their names.

I discovered them all: Robert Smithson, Cindy Sherman, Chris Burden—Jeff Koons, of course—we are very good friends. I gave them their start, I gave them money, so they would have a few dollars while the accountant worked on the books. That could take a very long time, and there was not always much money left for the artist. I took care of them out of my own pocket. Many times, I gave them ideas for their art. Artists don’t like to talk about that. That’s fine—I don’t do what I do for recognition. I’m satisfied with the commissions. But it’s not always what it looks like.

Chris Burden, I never got along with. I wanted to shoot him, but I didn’t have a gun. And what did he do? He went ahead and found someone with a gun, and asked him to shoot him. The man missed. He just got a little of his arm. But he used my concept.

Adrianne Geffel, I introduced to the world. I gave Adrianne Geffel her premiere at my gallery, with the artist Ann Athema. I gave Ann Athema her first solo show at the same time. So many things, I started. So many more I could have started, but somebody did them first.

And that’s all I can tell you about Adrianne Geffel. She was very grateful to me. She admired me very much. For that alone, you could say she was not unusual. But I was very happy to have the opportunity to introduce her. That led to so many things over the years, and now this book. It’s amazing to think—you and I would not be having this conversation right now, if I weren’t here with you.

[Kalman is asked to recount how he came to present Adrianne Geffel in a gallery setting.]

I remember, I first got the idea to put music in a gallery after seeing Steve Reich perform in a gallery. That’s how the concept came to me. Ann Athema was happy with the idea to have Adrianne Geffel play at her show. We had no piano, of course—it was an art gallery. It wasn’t the Copacabana. So we used an electric keyboard that Reich brought for us to use. He charged us only for the moving.

Available September 22, 2020.

Ann Athema:

Armutt, because he changed his name, thought I should change my name, too. Armutt thought everyone should find a new name and become a new person. He would say, “In the future, everybody is going to change their identity every fifteen minutes.” I said, “I see, and now you’re Andy Warhol. In fifteen minutes, could you please become someone more original?”

Armutt came up with the name Ann Athema for me. Like “anathema”—get it? Hardee- har-har-har. Armutt was the great avant-garde punster. There was a fellow named Bob Sheff around then—he was a Texan and played blues piano in a bar band. Armutt renamed him Gene Tyranny—T-Y-R-A-N-N-Y—and he became a thing. Armutt was trying to find somebody to call Kurt Vile—V-I-L-E—but no one went along with it, because they didn’t get the reference. Years later, I saw that a singer was going by the name Kurt Vile, but it turned out that Kurt Vile was the guy’s real name. Armutt was furious.

I liked becoming Ann Athema, actually—it was ludicrous. I thought of going with Irma Neutica, but Armutt was working with a drag artist he was grooming to call Irma La Douche, so Irma was taken. Working in public under the guise of Ann Athema allowed me to function without creative pressure, protected by the armor of irony.

Geffel was a different creature entirely. I was a nest of insecurities and anxieties hiding behind a joke name, making joke art. Geffel was pure truth and openness. Her emotions were her music, and her music was absolute emotion. I never experienced anything like that.

We arranged for Geffel to play at the opening of my show at K. Lewitt, and she ended up playing at the gallery every night for a month or more, I believe. I thought she would be a good fit, because the whole idea of art and music then was to do things that didn’t fit together. Trisha Brown was walking up the side of the building in an alley down the street. Larry Rivers was painting while he was playing the saxophone and making a plaster cast of his dick at the same time. No, if you want to know—I wasn’t there to see that, luckily. But I do know people who have seen the plaster cast, and a lot more people who have seen the dick.

I told the gallery I wanted no canvases on the walls at all. I would describe the art, and that would be the art. The galley people were ecstatic, in the diffident and alienating way gallery people experienced ecstasy, and I saved a lot of money on canvases. Before the doors opened, Geffel paced around the gallery, looking over the empty walls, humming to herself. She said to me, “I hope you know, Koshka, I can’t promise to match the spirit of your artwork.”

I said, “I know, Geffel—I’ve heard you play. That’s why you’re here.”

She made that odd little smile of hers, and she said, “Hey, Koshka—thanks.”

The opening of the show was fairly well attended. There were twenty or twenty-five people there—all the people who went to every opening, to ogle one another and be seen by one another. The director of the gallery introduced me, and I walked slowly all the way around the room and pointed to empty spaces on the walls. I said, “This is one of the earliest pieces in this series. It is the secret of life, pretending to be the secret of death.” I gazed at the wall for a moment and walked a few feet, and I said, “This is the earliest childhood memories of everyone here tonight superimposed over the worst fears of everyone coming here tomorrow.”

When I had covered all the wall space, I thanked people for coming and told them to enjoy the art while they listened to the music of an important new composer. I introduced Geffel, and she started playing a little electric keyboard the gallery rented from Steve Reich. Within a few minutes, everyone in the galley had gathered around her, watching her and listening intently.

Geffel was terribly nervous, and that only made the music more . . . like Geffel’s music.

Reviews:

Is a female artist's rage liberating or simply another symptom of oppression? The question is posed in "Adrianne Geffel" (Norton, 207 pages, $25.95), the clever first novel by David Hajdu, who is best known for his music criticism and the popular history of the New York folk scene "Positively 4th Street" (2001). His heroine is a small-town Pennsylvania girl with a rare condition called psychosynesthesia, which means that her mind is perpetually producing music that changes to reflect her emotional state. So long as Geffel is nervous and uncomfortable, she's capable of improvising astonishingly violent and dissonant piano compositions that make her a cult icon—"the new Queen of Bleak Chic"—in Manhattan's avant-garde demimonde in the 1970s and '80s.

Mr. Hajdu frames the novel as an oral history compiled by Geffel's would-be biographer some years after her abrupt and mysterious disappearance. The interviewees include Geffel's overawed parents, her martinet Juilliard instructors and a congeries of pompous musicologists and critics. All of them, and especially Geffel's noxiously controlling manager, try to claim credit for her genius, each basking in the glow of reflected relevance. "We push the envelope," brags her self-important record producer. "We pull the envelope. We tear it apart and smash it up into a little ball."

The sexism, the mind games, the exploitation—all of it ensures that Geffel's music is radical and subversive. But when she reunites with a lost love from her home town, melodic sweetness enters her playing. A critic compares a new composition to Debussy's "Clair de lune," but he means it as a devastating insult, a descent into the "glistening, vacuous treacheries of joy." Geffel's well-being is career-ending. In certain circles, there's no quicker way to discredit a woman's art than to say that it makes you happy. -Sam Sacks The Wall Street Journal

Music critic Hajdu (Love for Sale) dissembles with tongue firmly in cheek in his inventive debut novel, which takes as its subject the “Queen of Bleak Chic,” a piano phenom who breaks out in the early 1980s after withdrawing from Juilliard. Pianist Adrianne Geffel has a neurological condition that enables her to express her feelings through music. Geffel emerges through an oral history told by her family members who reflect on her troubled childhood (she ran away at nine) and others. Many try to exploit her talent, such as a pompous fellow student at Juilliard who positions himself as her manager, or claim to understand it (“Readers interested in how musical art evolves... will be intrigued to read future pieces by me on Adrianne Geffel’s music,” writes a critic). After the oral accounts catch up to the height of Geffel’s success in the mid-’80s, they turn to her disappearance at the age of 26 and gain greater poignancy. The author establishes Geffel’s impact on American popular culture from the very beginning (one can be accused of “only geffelling,” “over-geffelling,” or “not geffelling enough”), which makes the various accounts of her credible and engaging all the way to the end. Hajdu’s vigorous send-up of the late-20th-century music scene sings. - Publishers Weekly (starred review)

The eponymous heroine of this debut novel from Hajdu (Lush Life), music critic for the Nation, is a pianist of abrasive originality and persuasive power who hears music playing constantly in her head and shares it with the world. Adrianne grows up humming yet reacts violently whenever she hears other music played—it clashes with her own music—and after puzzling family and friends in her small town briefly ends up at Juilliard. Soon, she’s downtown New York’s “new Queen of Bleak Chic,” but emotional reconnection with an old friend who truly cares for her makes her change direction, shocking acolytes, and vanish before a key concert. The story unfolds as oral history, delivered mostly by those who celebrate their stake in her—her clueless parents, a controlling self-styled boyfriend—resulting in a portrait that’s as much about the exploitation of the gifted as it is about the gift of music, of the artist’s exterior situation as it is of the artist’s interior world. Hajdu is excellent at articulating the vitality of Geffel’s music while leaving what it actually sounds like to our imagination. VERDICT A reverberant and eye-opening portrait of an artist going her own way and finally saving herself; highly recommended. -Barbara Hoffert Library Journal (starred review)

This playful, poignant, and often very funny oral history parody tells the (fictional) story of Adrianne Geffel, an American pianist and composer who disappeared from public life in 1985 on the night she was to perform at Carnegie Hall. Music critic and cultural historian David Hajdu pretends to interview the people who were closest to Geffel—her parents, teachers, contemporaries at Juilliard, girlfriend, and music industry execs—to shine light on why a musician, whose work was “so powerful, so disruptively unshakable,” might vanish. Hajdu never finds out where Geffel went, but he constructs an indelible portrait of an artist who struggled with a rare neurological disorder that causes its sufferers to hear music nonstop. We find out that Geffel coped with her condition by putting what she heard in her mind down on the keys of the piano, making idiosyncratic, emotionally charged “music that’s not music.” Listeners raved about her unique sound until she fell in love and her compositions turned as placid as Debussy’s “Reverie.” If all of this sounds somewhat convoluted and leaves you questioning what’s fact versus fiction, that all serves Hajdu’s sophisticated satire, underneath which lurks many sharp insights into the music world. - Adrienne Davich, VAN magazine

Known for his excellent books on music and pop culture, including Love for Sale (2016), Hajdu presents his first novel. Written in the form of an oral history, it presents Adrianne Geffel, a brilliant young pianist and composer who gains fame and accolades for her arrhythmic avant-garde music. She also suffers from a rare neurological disorder. She became so fame famous that her "name had fallen into common usage" and thus the "lingua franca of American culture." Since she remains an elusve figure, her life and career are revealed through interviews with her family members, romantic partners, music teachers, and musical team. Hajdu has fun name-dropping real-life artists (Sophia Coppola, George Saunders, Susan Sontag, Twyla Tharp) and making light of academia in the satirical mix. This may remind some readers of Rick Moody's work (one of his stories takes the form of liner notes), while the enigmatic Geffel has elements of Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, and Lou Reed. Hajdu has created a weird and strangely wonderful fictional evocation of New York's 1970's and 1980's underground music and art scenes. - June Sawyers, Booklist

A faux oral history of a sui generis performer in New York's avant-garde music world.

In books like Positively 4th Street (2001) and The Ten-Cent Plague (2008), Hajdu explored how counter-cultural folkies and comic-book artists rattled conformists in the 1950s and '60s. For his first novel, he attempts to do much the same for 1980s experimental music. Adrianne Geffel, we're told early, is a household name thanks to her passionate and defiant nature, possessed of a prodigious talent and impatience for musical strictures. Plus, a mysterious disappearance established a mystique that got her name-checked by the likes of Cardi B and George Saunders. The oral historian doesn't have access to Geffel herself, instead piecing her life together through interviews with family members, teachers, critics, and participants in New York's downtown scene who prized intellectualism and a certain abrasiveness. (Susan Sontag and Twyla Tharp were eager to witness this "doyenne of downtown music.") Despite (and thanks to) Geffel's idiosyncrasies, she was accepted into the Juilliard School, caught the ears of highfalutin Village Voice and SoHo Weekly News writers, and seemed destined to rise to the semi-fame of a Steve Reich or a Philip Glass. In truth, though, Geffel is something of a MacGuffin, a way for Hajdu to satirize the kinds of people who can't appreciate genius when it's right in front of them or wish to exploit it: the critics, the Oliver Sacks-like neurologist, the sketchy self-declared manager, the record-label executive. It's funny stuff, even if the targets are easy, though more of Geffel's presence would've been welcome. Writing fiction whose central character is a cipher presents a challenge to even the most accomplished novelists (see Myla Goldberg's Feast Your Eyes and Alan Hollinghurst's The Sparhsholt Affair), and Geffel's own voice would've bolstered Hajdu's mythmaking.

An entertaining satire about a music genre not typically known for its humor. -Kirkus Reviews

"Her records are a free assault on everything that recording itself represents,” notes a fictional Village Voice music critic in David Hajdu’s novel Adrianne Geffel. He’s referring to the title character, a virtuoso pianist whose avant-garde improvisation rocks the lofts of 1970s SoHo. And he means it as a compliment, recalling “outbursts so vital, so mind-rattling, soul-fuckingly extreme that they burst out and fly straight through you and out of your room.” The novel purports to be an oral history, driving home Adrianne Geffel’s cultural impact by referencing records that had to be heard to be believed, an unauthorized semiautobiograpical film, even an eponymous verb, to geffel (meaning “to release pure emotion in a work of creative expression”) and her mysterious disappearance, unsolved to the present day. The odd historical reference aside, Adrianne (and every other character “interviewed” for the book) is a figment of the author’s imagination. Together, these interviews form a postmodern account of a postmodern pianist, an outspoken chorus in which her own voice is absent, at once obscuring and illuminating her.

Hajdu, himself a reviewer of music, movie, comics, and culture at large, brings a kind of comic book sensibility to his first novel, which resembles a music biography. Though relatively short, the book is heavy on illustrative details and quirky pulp sensibility. Unfolding from the perspective of a faceless oral historian interviewing a series of subjects, the point of view is disciplined in a way that recalls a comic book penciler’s control over a panel’s field of view. Like a traditional biography, the novel starts in Adrianne’s early childhood and proceeds chronologically through her life. As a baby she hums complex original melodies, yet the slightest musical phrase— an overheard radio, a live instrument, even recordings of her own voice—send her into a fury of atonal, violent rhythms. Her parents, who are wholesome if not especially culturally literate (“I love movie musicals, even when they’re on the stage,” says her mother, about a class trip to Broadway), are perplexed by their child’s mercurial rages. Slowly, her teachers and friends realize that Adrianne is reacting to music she hears in her head, music that reflects her emotions. When sounds in the real world are discordant with that music, the dissonance forms a feedback loop that makes watching a movie or attending a school dance a traumatic experience. But why? Everyone in the book has their own hypothesis: Geffel’s parents speculate about her baby formula, and the propane tanks they stored above her bedroom. Her teachers believe that if they could only give her the right environment, the right resources, her potential could bloom. Her doctors diagnose her with psychosynesthesia and consign her to music therapy as a cure. Her aunts, meanwhile, believe she is possessed.

Adrianne is introduced to the city through the prestigious, imperious world of Juilliard, presented here as an old boys club for those of a certain social status. (As for campus life, the students were simply “required to practice their instruments, and beyond that, to be breathing.”) Adrianne’s time studying piano is cut short when, at a recital, she plays harsh atonal melodies instead of the sheet music in front of her—a manifestation of her emotional discomfort—and is sent to a mental institution. There, she meets a conceptual artist, and, upon her release, springs onto the music scene, playing uprights in art galleries and grand pianos in lofts where she is hailed as an avant-garde hero. Her music reflects the stress of performing in an alien world, the emotions manifesting in an eruption of nervous sound. This style becomes Adrianne’s hallmark and brings her fame—but none of the people around her consider how this intensity might impact her mental health. One of her few true friends, a conceptual artist who goes by the name Ann Athema, observes that in a performance “Geffel was terribly nervous, and that only made the music more…like Geffel’s music.” It is in Ann Athema who Adrienne confides about the internal torment that leads her to perform the music she does. “I’m a nervous wreck when I’m doing it, and that only seems to make it more successful. I feel awful, and so I make awful-sounding music,” her friend recalls her saying.

With the wisdom of hindsight and curated narration, we see how the people around Adrianne ignored this strain, leaving her vulnerable to a fellow Juilliard student–turned music producer who exploits her talent and corrals her into a pseudo-romantic relationship. We witness her father’s standoffishness, and her mother’s inability to help her daughter navigate the world. Meanwhile, Adrianne’s classmates and instructors care more about promoting themselves than they do about her wellbeing. A doctor who treated Adrianne uses the interview as an opportunity to plug his book, as does her piano instructor, and the music critic who’s seeking a publisher for a collection of his reviews of her work. In the same vein, several characters all claim to have discovered Adrianne, or to have created her. As one critic puts it, perhaps mirroring a phenomenon Hajdu has observed in his own work as a critic, “Since her music was so unique and stood outside the standard categories, writers on every music beat felt free to grab a piece of her….The arrogance was appalling.”

Barbara Lucher, Adrianne’s high school best friend and later romantic interest, acts as a kind of counterbalance to these unrepentant pedagogues. Teaching her how to block out the music of the world with earplugs and scarves, she protects Adrienne, and helps her have a normal-enough high school experience. Later, they move in together, lofting their bed over a piano and joining the “big lesbian hangout” of the Village. With Barbara around, the music in Adrianne’s head is gentle, lyrical, and soothing. But the critical establishment of the time—a group of (notably all male) producers, reviewers, and critics—declares that the music she produces during that happy period isn’t radical or avant-garde. These critics believe that her music, a mirror of her emotions, is only good when she is struggling. Though she is far from the first artist to wrestle with fame, Adrianne’s distinctive musical abilities, and the emotional transparency of her music, make these tensions uniquely visible. Hajdu’s book can be read as the story of a critic grappling with the destructive forces at play within his own field.

After seven years of performing in Manhattan, Adrianne makes the choice to leave. Skipping a career-defining recital at Carnegie Hall, she disappears. But, remembered as a musical oddity, a pure emotional force, an icon, it’s hard for the music world to let her go. The closing pages of the book consist of a bulleted list of theories about where she is now, culled from listservs and Twitter, each more outlandish than the last. Adrianne is rumored to have started a farm, performed in a mask and cloak under a different name, started a band called Monkeyz using digital avatars, or moved into Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed’s back yard. Talked down to, manipulated, written off as possessed and mentally insane—is it any surprise that Adrianne Geffel opts out? In the end, Adrianne Geffel is both a love letter to cultural criticism and avant-garde art, and an intimate indictment of the same. - Taylor Poulos, Guernica

Prepare to be “geffelled” — literally.

While various forms of the word “geffel” have become part of the American vernacular, all referring to unrestrained outpourings of emotion, little writing has explored the living, breathing artist who inspired it. Finally, Adrianne Geffel comes to life in David Hajdu’s oral history biography of the avant-garde pianist and composer. Though conferred legendary status, too little of Geffel’s work gets listened to intently. What higher praise could there be for a book about music than to say it will send you to the streaming services, record shops and YouTube eager to reevaluate Geffel’s recorded output? In a career divided, is her true genius revealed in the often dark, atonal early live albums “So Far, SoHo” and “Oh, Negative” or her more tranquil, melodic pieces that begin to appear in the second set of her famed 1983 Merkin Concert? Whatever your opinion, as noted in the author’s introduction, “Put plainly, with no hyperbole, [Geffel’s] music is not to be believed.”

Which seems the perfect moment to reveal that, no, you haven’t been living under a rock lo, these 40 years since Adrianne Geffel’s recording debut. Instead, you have been introduced to the, at times hyper-realistic, yet fictional world created by David Hajdu as mock-biographer. At turns parodic and satiric, “Adrianne Geffel: A Fiction” works because it shares such a believable story. Even if the title character is meant to remain a bit of an enigma, her clueless mother, childhood piano teacher, Juilliard professors, doctors, record label representative, reviewers, friends and quasi-manager often feel all too real as they recount their often-pumped-up roles in Geffel’s life. While clearly meant to be humorous, the story spins in such interesting directions that it feels unfair to reveal too much of it. Suffice to say that musician biography tropes get gloriously twisted in this seemingly traditional tale of the sensitive, put-upon artist.

Fans of the genre, as well as musicians, will probably enjoy Mr. Hajdu’s humor most. Through his characters’ voices, the author takes jabs at everything from music teachers who value formality and technique over authentic creativity, to cronyism influencing conservatory admissions, to music reviewers using elevated language and obscure references to say precious little. Especially savage is his portrayal of Infiniti Records’ executive vice president Harvé Mendelman. This empty suit crows about starting his label’s “Archive of Anomalies of Musique Mechanique” series as a means to release technically flawed, nearly unlistenable material — he slaps on liner notes from a verbose, self-important New School professor and delights in even modest sales for his supposedly adventurous “avant-line.”

Biran Zervakis, the book’s greatest villain, is drawn wickedly enough to inspire winces and snickers from anyone. Biran, pronounced “like Lord Byron…not Brian,” takes advantage of happenstance, then wildly oversteps in trying to promote and exploit his quirky, relatively naive Julliard classmate. “My Adry,” he calls her, treating her very much like a possession even as he fails spectacularly to ingratiate himself with anyone but the sleaziest of businesspeople and a maybe-gullible-maybe-conniving secretary. His evasiveness, double-speak and malevolence grate — purposefully and amusingly.

Geffel’s friends Barbara Lucher and Ann Athema offset Zervakis’ smarminess nicely. While the satiric nature of certain characters keeps them at arm's length, Lucher and Athema elicit laughs while remaining more realistic and likable. Lucher, Geffel’s best high school friend, steps up for her pal at all the right times, especially when Mr. and Mrs. Geffel steer their daughter toward underwhelming college choices given Adrianne’s musical gifts. Lucher later returns in the nick of time to rescue her friend, ever her faithful, and wildly profane, defender. The visual artist Athema (yes, it’s a purposefully-picked pseudonym) meets Geffel under less-than-ideal circumstances during her college years. She, too, recognizes Adry as both a genius and human being and helps her new friend navigate the rule-bound underground New York City art scene.

Ultimately, just as Adrianne Geffel’s work inspires both high and low art (a Whitney Museum exhibit entitled “Impulse and Impetus: (Re)Imagining Adrianne Geffel” and a Cardi B namedrop in a “number-three pop hit”), Mr. Hajdu’s book makes jokes both heady and base. They all work to remind us that music and art matter, but the process that brings them to the public’s attention is often as capricious and cruel as that of any other business. Also, the greater the talent and originality of an artist, the more the conformists will try to restrain them and the unscrupulous will pounce and take advantage. That Mr. Hajdu delivers such bleak views so wittily helps make some sad truths feel satisfying. Plus, an ambiguous conclusion leaves readers to decide just how “geffelesque” Adrianne’s ultimate fate proves to be. - John Young, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The truly witty satirical novel is a rara avis, possibly because satire is most effective when carried out by stiletto thrusts, delivering fatal wounds that are initially hardly felt, rather than by repeated clubbing. Maintaining a consistent lightly satirical tone (as in, say, The Diary of a Nobody) over novel length is a considerable achievement, but David Hajdu has succeeded in doing just this with Adrianne Geffel.

The eponymous heroine of his work is a musical genius, a pianist with a rare neurological condition that results in her hearing music constantly in her head that she is able to channel, unmediated, into freeform pieces that have a visceral effect on her listeners. Known to the music press as the ‘Queen of Bleak Chic’ or the ‘Geyser of Grand Street’, she is (briefly) celebrated by the cognoscenti of New York, streaking across the city’s artistic firmament like a comet, before disappearing in mysterious circumstances.

Purporting to be an investigation by a writer who never met her or heard her perform, the novel consists of a series of interviews with Geffel’s parents, music teachers, record-company employees and music journalists, all of whom unwittingly parade their various vanities, misunderstandings and tawdry self-interest in their answers to the questions put to them. Alongside these interviewees, however, there are a few ‘genuine’ heartfelt contributions from true, disinterested friends, chief among them Geffel’s lover, Barb Lucher, whose every statement skewers the exploitation and greed surrounding the pianist.

At once delightfully mischievous (Geffel’s parents’ obsession with liquid propane and her brother’s narcissism are a constant joy) and fundamentally serious (she falls victim to a talentless self-appointed agent and an unscrupulous record-company boss), Adrianne Geffel will be enjoyed by anyone (with a sense of humour) interested in the interface between artistic genius and the commercial world. Or just anyone with a sense of humour. - Chris Parker, London Jazz News

David Hajdu knows music. As the biographer of Billy Strayhorn (“Lush Life”) and chronicler of both pop (“Love for Sale”) and folk music scenes (“Positively 4th Street”), he has an intimate and thorough knowledge of not only the artists but also the producers and promoters, critics and fans who populate the music world. It makes sense, therefore, that Hajdu would set his first work of fiction in this artistic milieu. But while much of his nonfiction necessarily centers on the stars, “Adrianne Geffel” focuses instead on the periphery. Although this novel is a purported oral history of the title character, a mysterious avant-garde musician, hers is the one voice we never hear. Instead, as we seemingly learn about this fictional pianist-composer we are treated to a revealing — and at times hilarious — satire of the music business, fame, and the cult of personality.

The setup is simple. After a brief introduction, which assumes we are already aware of the genius of the fictional Geffel, the unnamed narrator expounds on her societal impact. He places her, Zelig-like, with various cultural touchstones: Geffel is the subject of a Jill Sobule song, the unnamed author says, and has “inspired” a “semi-factual, semi-fictional” Sofia Coppola film. She is referenced in an off-color Cardi B lyric. He then presents interviews with family members, teachers, friends, lovers, critics, doctors, and business associates cut and compiled to create a portrait of the musician, who has apparently disappeared. As the interviews alternate, they sketch out the biography of a misunderstood artist. More to the point, they expose the blinding narcissism of nearly everyone drawn to her strange art, skewering the institutions that define and market taste.

Much of the humor in this short comic novel is broad. Geffel’s mother, Carolyn, may have proudly framed one of her daughter’s albums, for example, but she hasn’t played it. “I’d have to take it off the wall and unframe it, and get the record player out,” she explains. A music critic, meanwhile, can’t resist claiming credit for Geffel’s genius. “[P]eople forgot the importance of my role in introducing her, until I reminded them,” he says. Pompous scenesters baldly remake themselves to sound more interesting — a Brian becomes “Biran,” “like Lord Byron … Brian’s just my legal name,” he explains, while a grasping record executive spells his name “Harvé.”

Inside jokes abound, particularly in the testimony of experts who can supposedly offer insight into Geffel or her exceedingly odd compositions, which apparently emanate directly from her emotions. Anybody who has interviewed musicians, for example, will recognize Hajdu’s parody of a spacey saxophonist, who responds to a question about his collaboration with Geffel with oblique incoherence: “We created in the same time and space,” he says. “We did not listen to one another in the historical sense.” That same wit takes down academic language when a verbose musicologist unintentionally reveals his own cluelessness as he says, “The sheer volume of scholarship on Adrianne Geffel since recordings made her music available for close examination speaks at once to the emotional-intellectual capaciousness of the work and to the inversely proportionate illuminative capacity of the musicologists engaged in unpacking it.” Likewise, an early reference to an editor at Boston’s now-defunct Real Paper will have local music journalists guessing at its inspiration.

Other jokes are a little more welcoming to a wider readership: When that music critic, who tries to take credit for Geffel’s fame, quotes his own first review of her — “I have seen the future of the avant-garde, and her name is Adrianne Geffel” — it’s an obvious reference to Jon Landau’s similar lauding of Bruce Springsteen, for example.

At times the humor wears thin. The one-note recitals, particularly by the hypercerebral musicologist and self-important critic, become repetitive, even in this relatively short work. By the time Hajdu wields the critical doubletalk to tackle another issue — whether if great art can be created by someone who is happy — it is too little too late. A perennial debate among critics and fans of a certain sort, this question is left largely unresolved, though Hajdu does use it to hint at Geffel’s fate. What we learn, instead, is how all of us view each other as extensions of ourselves, for our own dreams and purposes, and, ultimately, how mysterious art and the act of creation really are. - Clea Simon, Boston Globe