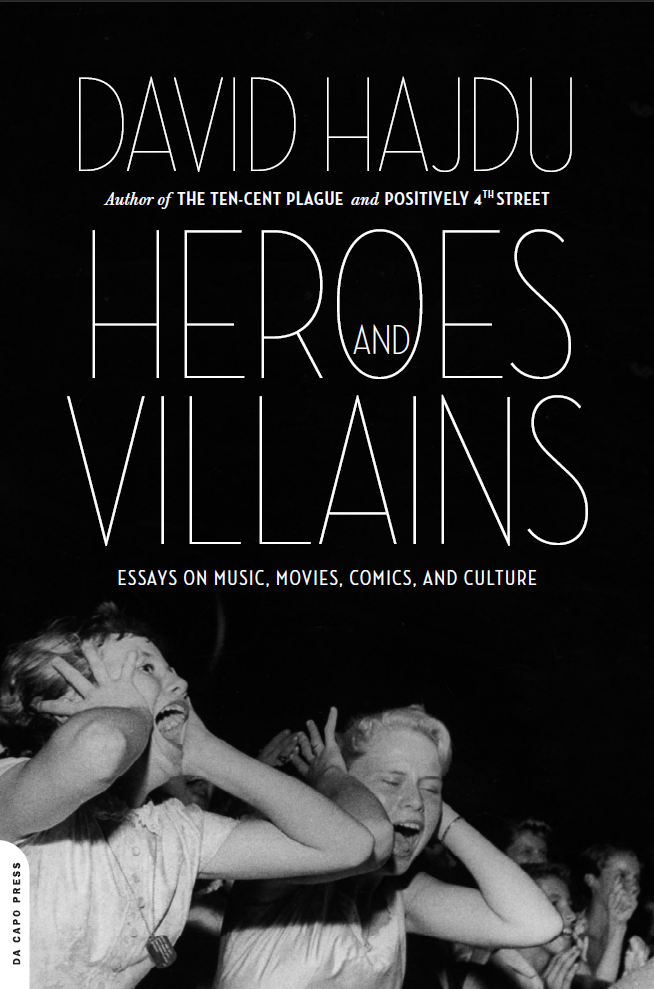

Heroes and Villains: Essays on Music, Movies, Comics, and Culture

Heroes and Villains is the first collection of essays by David Hajdu, author of Lush Life, Positively 4th Street, and The Ten-Cent Plague. Eclectic and controversial, Hajdu's essays take on topics as varied as pop music, jazz, the avant-garde, graphic novels, and our downloading culture.

The heart of Heroes and Villains is a piece of cultural rediscovery, original to this book. It tells the untold story of one of the most important — and, ultimately, one of the most tragic — figures in American popular music, Billy Eckstine. Through exhaustive new research, Hajdu shows how this great, forgotten singer, once more popular than Frank Sinatra, transformed American music by combining sex appeal, sophistication and black machismo — in the era of segregation. The cost, for Eckstine, was his fame.

Other essays in this expansive book deal with subjects including Beyonce, Leonard Cohen, Elvis Costello, Bobby Darin, Will Eisner, Elmer Fudd, Philip Glass, Woody Guthrie, Anita O'Day, Harry Partch, Marjane Satrapi, Kanye West, the White Stripes, Joni Mitchell, John Zorn, and more. (This text courtesy of DaCapo Press.)

Excerpt:

The Billy Eckstine Orchestra was a startling, fearless, intelligent, sexy group — the Clash or NWA of its time. To a generation of jazz enthusiasts and musicians accustomed to the infectious dance beats and buoyant riff tunes of the swing bands, the angular rhythms and vertiginous instrumental solos of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, and others under Eckstine were a musical catharsis. "I never heard nobody play that," Art Blakey once said. "The only big band I ever liked was Billy Eckstine, 'cause everybody in that band could play. Now, that is a jazz orchestra!"

There is some film footage of the group, shot in 1946 for the Negro-circuit movie short Rhythm in a Riff. Eckstine looks virilely debonair, swaying on the bandstand so languidly that he's almost out of time, while the orchestra rages behind him. The high musical standard drops only when Eckstine solos on the valve trombone, teetering off pitch. More than fifty years after the footage was shot, the music sounds utterly contemporary, like the jazz being played in a good club tonight.

That is to say, it was unfamiliar and challenging to the public and the critics of its own time. Dance audiences would stand still on the floor, confounded. "We tried to educate people," Sarah Vaughan recalled. "We used to play dances, and there were just a very few who understood who would be in a corner...while the rest just stood staring at us." The idea of sitting down and listening to a jazz orchestra as one would to a symphonic one was not unprecedented, but it was still a novelty and largely reserved for special events in formal settings legitimized by white society, such as Ellington's annual concert at Carnegie Hall.

Eckstine found the cultural terrain too rocky for trailblazing, as he told various interviewers over the years: "We were doing new things. People were used to dancing, and they couldn't dance to it. They just stared at us — some with distaste....We knew we had a great band. But it was a little too new for people....It was...new usages of chords in harmonic structures that had never been done before. And for that, we would get a lot of heat from different critics because they didn't know what the hell we were doing. But the younger people loved us and the musicians were just agog with that band....Most of the jazz critics roasted us. They said the band was out of tune because we were playing flatted fifths and flatted ninths, and it was strange to their ears."

Reviews:

David Hajdu is a cultural commentator with a generous spirit and lightness of touch; but when it comes to mediocrity he lands a sucker punch. Empty posturing, artistic commodification and media faddism must all face the force of his opprobrium, not to mention talent corrupted. Heroes and Villains is an entertaining collection of Hajdu's journalism from the past few years, including book and album reviews, obituaries and opinion pieces, much of it first published in the New Republic, for whom he is chief music critic.

Hajdu's "heroes" include and array of characters from the versatile actor-cum-rapper Mos Def to W.C. Handy, a bandleader and composer who, at a Mississippi rail station in 1903, overheard a black musician strumming a guitar with a knife blade. "The weirdest music I had ever heard", wrote Handy — "thereupon documenting the earliest known performance of the blues", wirtes Hajdu. The evolution of blues is a recurring theme in a collection that traces an arc through twentieth-century American racial politics. Hajdu reflects on the bebop pin-up Billy Eckstine, once "the most popular male vocalist in the country". Eckstine ended his life washed up and penniless, his brief star having been extinguished by a "white-controlled entertainment industry at once obsessed with and fearful of black male sexuality". Hajdu contrasts Eckstine's fate with that of "funny, sexless novelty figures" such as Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller, and, in a later essay, with Ray Charles, sexualized but blind ("his Ray-Bans shielded him"). Elsewhere, Hajdu pays (measured) tribute to various comic strip artists (Joe Sacco; Will Eisner; Marjane Satrapi), the French-Italian pianist Michel Petrucciani, Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen (though not Philip Glass, with whom Cohen has collaborated), and the under-loved Warner Bros creation Elmer Fudd.

Equally stimulating are the sketches of "villains", a cast including Sting (in his "outsized smugness"), Starbuck's reductive "entertainment" division, MySpace (which "conspire[s] to inhibit originality while rewarding familiarity and accessibility") and Thomas A. Parker (aka "The Colonel"), whose "pitiless lordship" of Elvis Presley helped to stunt the performer's acting career and create today's mythological monster of garishness and rhinestone. Hajdu laments the decline of Brian Wilson and pours scorn on the White Stripes ("a two-person, one-man band", whose tracks "sound like demos — or, occasionally, rehearsals for demos"). More provoking still are his gilded damnings. Here he is on the composer John Zorn: "an enigmatic provocateur with an outsize mystique who stirred acolytes to do work better than his own". The same, remarks Hajdu with airy sagacity, could be said of Erik Satie. - Times Literary Supplement

David Hajdu's new collection, Heroes and Villains, is packed with shrewd, original observations about subjects ranging from Elvis Presley to Elmer Fudd, from Kanye West to (well, whattaya know) Taylor Swift. Over the past decade, Hajdu has established himself as an ambitious, wide-ranging critic and biographer.

The essays in Heroes and Villains are most often critical assessments mixed with biographical sketches, a rare form in this time of the short review and the widespread assumption that readers will be confused upon encountering an actual opinion in the midst of a profile. Hajdu is the rare first-rate critic who's also a first-rate interviewer—he's rarely interested in putting his own opinions ahead of the stated intentions of the artist under discussion. If the critical appraisal is at odds with the good quote, he lets both stand, and a fresh tension is the result.

In writing about Joni Mitchell, for example, Hajdu reports that the singer-songwriter insisted to him that she'd always been a jazz artist, never a folk singer, a notion Hajdu takes quiet but firm issue with in proceeding to give a brief but thorough overview of her career, tracing her (yes) folk period, her jazz period, and her subsequent electronic experiments and, most recently, her re-recordings of some of her best-known songs. It takes a hardy critic to plow through much of Mitchell's latterday work, and Hajdu listens to this music with a typical clear ear canal.

In his introduction, David Yaffe compares Hajdu to Otis Ferguson and Edmund Wilson, and I would add that he's also working in the tradition of Gilbert Seldes or Robert Warshow, cultural critics who took the long view without standing aloof from pop culture. Hajdu's writing is always generous. Even when he's listening dubiously to Josh Groban ("a wondrously strange living amalgam of imposed ideas about pop artistry, most of them fearsomely cynical"), he can find time to describe his voice as "an airy, robust baritone… an impressive instrument well employed to impress."

Now that's a good critic. - Ken Tucker, Entertainment Weekly

In his autobiography, Miles Davis called musicians Dizzy Gillespie, Buddy Anderson and Art Blakely by their names, but he referred to Billy Eckstine simply as B. (He described B's sound as the "greatest feeling I ever had in my life—with my clothes on.") Profiling Eckstine in his new book Heroes and Villains, a collection of essays on music, movies, comics and culture, David Hajdu writes, "If Miles Davis represented the birth of the cool, Billy Eckstine was its conception."

The title of Heroes and Villain's lead essay, "The Man Who Was Too Hot," is a double entendre for Eckstine's music; B rejected the orchestrated precision of big band music, and his sound was a forbearer of bebop ("jerky" and "over-stylized" said Variety in 1946). The title's second meaning is for the handsome Eckstine's status as an unapologetically romantic, black sex symbol whose appeal to white women ultimately ruined his career.

Hajdu, the music critic for The New Republic and a professor at the Columbia University School of Journalism, mainly focuses on the latter implications of his title: how a double-page photo in Time magazine sabotaged Eckstine's career. The photo in question depicted shrieking white women (perhaps part of fan clubs "Girls Who Give In When Billy Gives Out" or "The Vibrato's Vibrators") clawing at the musician, and it found B barred from clubs and compromised his once-promising Hollywood film contract—downgrading it to a few peripheral roles that were edited out for Southern versions.

Yet Eckstine's musical tragedy, of being too hot, is a uniting theme of Hajdu's work, which in its best moments explores the edges of musical and cultural classifications and formally defined eras. Eckstine's sensibilities were too hot for what was desirable in the 1940s and 1950s, while his talents—as a voice and band leader, but not a musician who could actually play bebop or rock and roll—were too limited for the eras that followed.

Interpreting what to make of this cultural edge between eras, or even what to call it—bop? rock? pre-rock?—has been a particularly thorny issue of late. Following the deaths of Bo Diddley and Les Paul this summer and last, it's obvious that we still greatly misunderstand the music of their particular edge, on which Eckstine was a fellow traveler. This error comes either literally in the case of Bo Diddley, whom The New York Times referred to as Mr. Diddley in his obituary, or thematically in the case of Paul, who stymied deejays everywhere when it came to proper musical tributes (to play the plain and popular duets with his wife; the restrained, shackled riffs behind Bing Crosby; or the rarely recorded experimental stuff that made him a legend?).

Their misunderstood era and countless others are fertile ground for Hajdu. His other essays examine subjects such as the American songbook and Mos Def, a multi-platform talent overshadowed by hip-hop's rise to mainstream status; the flashbulb life of the enigmatic Bobby Darin; the dual racial and musical lives of Sammy Davis Jr.; and Brian Wilson's attempt at singlehandedly willing a post-pop form of American music into existence (before drugs and his own context stopped him). Each is a well thought-out query into being too hot for the contemporary yet unable to invent the future.

Best put, the subjects are the sort, as poet Matthew Arnold wrote, "wandering between two worlds, one dead/ The other powerless to be born." Hajdu's work is music and history scholarship disguised as popular writing: It explains why later movements and eras were possible.

Hajdu's affinity for comic books (read his The Ten-Cent Plague) makes appearances in the book, but Heroes and Villains is principally about music. Hajdu writes with clear authority and always has the correct reference, quote or example at hand. His strong referential style—bringing in obscure, far-flung yet meaningful examples and corollaries—is like a grown-up Chuck Klosterman, minus the cocaine.

He doesn't need to take controversial positions to prove his knowledge (he affirms Revolver as a better record than Sgt. Pepper); and his humor is subtle: A chapter on the music played in Starbucks begins with the line, "About 50 years ago, when the Soviets who survived Stalin began to accept the gift of his death, the state's cultural overlords started to loosen their choke hold on the country's music."

Each essay is under 10 pages and accordingly succinct. Yet the individual pieces, whether on Alan Lomax or Sting or Philip Glass, have a depth of research and information evocative of Eckstine's musical signature: speedy bebop that packs dozens of quality sounds into a bar the audience only expects four of five notes from. Heroes and Villains is dense, but it's hot. - Matt Woolsey, Forbes

I don't ordinarily review collections of essays, especially collections of previously published essays, but I don't want to miss the chance to tell readers just how interesting and accomplished a cultural critic David Hajdu is, and this, his first collection, is as good a place to begin as any.

Hajdu is music critic for The New Republic, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism and the author of several innovative books about music (Lush Life, a deserved resuscitation of long-time Duke Ellington collaborator Billy Strayhorn, and Positively Fourth Street, again about collaborations, those that produced the '60s, about Bob Dylan, but also about Richard Fariña). He's also the author of a very good book about comic books, The Ten-Cent Plague.Where Hajdu excels is in his ability to deal not just with acknowledged cultural forces; there are essays here on Ray Charles (nobody more central to the history of American popular music), Woody Guthrie, Elvis and John Lennon, but with figures generally viewed at the margins as well, conferring centrality upon them.

Take the opening essay, Billy Eckstine: The Man Who Was Too Hot. "Hot" carries a decidedly double meaning here: Eckstine, who was black and beautiful, was for a time as popular as Sinatra (12 top-10 hits between 1949 and 1952). But a double-page spread in Life magazine in 1950 changed all that. It showed the Adonis-handsome singer surrounded, Elvis-like, by worshipful girls — worshipful white girls. That more or less put paid to a career that was promising movie celebrity as well. So, too hot sexually, and too black; too hot musically, as well, since Eckstine straddled the edges of the big-band era and cool bebop, of which he was a pioneer (his own band was like an all-star team: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon). It's a sad and moving tale, spun out elegantly by Hajdu in a mere 15 pages. Here's a taste:

"Billy Eckstine defied the rules, changed them, and became a new kind of role model for generations of black singers, from Sam Cooke and Marvin Gaye to Diddy and Kanye West.… For them and their peers, expressing a savvy, daring, masculine black intelligence in music or film… is to play the game by the rules Billy Eckstine laid down."

It's tempting to indicate Hajdu's range and temperament by quoting extensively; there's no better way to convey the flavour of his work. But I'll limit myself to a few, chosen not quite at random.

Of the great Ray Charles, he writes that although he played piano "with the discretion of a sympathetic accompanist," his singing was "orchestral.… Charles's vocal intonation was so complex and nuanced that he could make a world out of a note. He rarely sang any note dead on pitch, but preferred to work in shades of microtones around the centre." And so impressively on.

Of consummate jazz diva Anita O'Day, who also drained the jazz life to its lees, he writes: "Boredom was the one thing that was intolerable to O'Day. Her music was the manifesto of her devotion to kicks at all costs. Ecstatic, indulgent, risky, excessive, and volatile, it was drug music, improvised in a state of simulated euphoria and imagined immunity."

Of Elmer Fudd (yes, that Elmer Fudd), whose "head is a fruit bowl of round shapes: honeydew cheeks, plum nose, cantaloupe eyes on a blue-ribbon crenshaw head," Hajdu writes: "In the 1950s, Looney tunes' creative use of Elmer as a negative force, a character through whom given ideas could be discredited by ridicule, approached cultural insurgency." A nice melding of aesthetic and cultural aperçus there.

He writes splendidly on Walt Whitman, blogging, the Iranian cartoonist-memoirist Marjane Satrapi, Joni Mitchell, Will Eisner, Dinah Washington, Mos Def, Brian Wilson's pop-transcending ambition (the title of the book comes from a Beach Boys song) and several dozen others. His Three Women in Pop: Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Lucinda Williams is culturally knowing and suggestive, and elevates Williams to the pop-goddess status she merits through her sheer, uncompromising humanness.

Hajdu writes always with fluency, wit and a confident mastery of his subject. Which is not to say there's anything of the know-it-all about him. Within that ease is a constant sense of generous discovery.

I've been reading this work compulsively for several days now. Go thou and do likewise. - Martin Levin, The Globe and Mail

I hate jazz. The music leaves me cold—yet perversely, I love the idea of jazz. I love the image of hip, swinging, subversive people who live by their own rules, who revel in melancholy, who blow sexy, dangerous notes in out-of-the-way places.

But I'm ready to give the genre a second chance, thanks to the wonderfully lustrous and effortlessly instructive essays in David Hajdu's sparkling new collection, "Heroes and Villains: Essays on Music, Movies, Comics, and Culture" (Da Capo). Hajdu (pronounced HAY-do) is a New Yorker who teaches at Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism, but in 2002-03 he was a writer in residence at the University of Chicago. The time on the city's South Side inspired him to write "A Hundred Years of Blues," one of the very best essays in this estimable gathering.

The city noses its way through many of these marvelous pieces the way the Chicago River threads itself under the succession of little bridges, all cool and blue and easy. In an appreciation of singer Dinah Washington, Hajdu notes that she was born in Alabama but grew up in Chicago in the 1930s "when the city was a hothouse of jazz, blues and gospel music, all three of which had also been transplanted from the South not long before then." Hajdu traces the familiar history of jazz, but with a poet's passionate yearning, not a scholar's bored yawn. He makes you want to rush out and get hold of the music about which he writes, no matter what you may have thought about it in the past. Clearly, you weren't alert to "the fire, the tension, and the surprise," in Hajdu's words, that this music kindles when it wants to.

And then there are the essays on other topics, such as rock music, comic books and cartoons. His essay on Elmer J. Fudd is a brilliant treatise on an animated anomaly. "His head," Hajdu notes, "is a fruit bowl of round shapes: honeydew cheeks, plum nose. ... " But Fudd's heart is what matters: "By nature open-minded, trusting, sensitive and forgiving, Elmer is congenitally ill-equipped to deal with Bugs, the image of savvy charm, quick wit, and resourcefulness, not to mention duplicity." Bugs Bunny is the hip headliner, but Fudd is the lovable Everyman. - Julia Keller, Chicago Tribune

In this collection, David Hadju presents a range of reflective, analytical assessments of key figures in the history of popular music.

As befits a professor of journalism, the assembled think-pieces are aimed at the more cerebral music enthusiast, focusing on the work of American mainstays including Sammy Davis Jr, Brian Wilson and Woody Guthrie.

Hajdu is erudite and opinionated, and he also examines films and graphic novels (his previous book, The Ten-Cent Plague, examined the impact of the comic book on American society).

The book is not without its faults; some of the content reflects an over-earnest attempt to appeal to a younger audience, containing references to MySpace, Starbucks and blogging that already feel passé.

Similarly, the acerbic side to his writing can become grating and his sniping at Beatles biographer Philip Norman feels unnecessary.

But the tone of the book is entertaining; a scholarly approach to pop culture that's both geeky and accessible. - Tom Hicks, Metro magazine

This meaty collection of musical essays ranges from Sammy Davis Jr via the Beach Boys to Philip Glass. The opening appraisal of the unfortunate Billy Eckstine, a singer and bandleader adored by Miles Davis, disinters a forgotten genius.

A paean to Rogers and Hart explores how they "brought the value of art to the realm of frivolity". But Hajdu's displeasure is equally enjoyable. He savages Sting's "forced, mannered quality", laments Joni Mitchell's loss of form, and explains Paul McCartney's failure to match early triumphs: "He's always been busy and productive, but he just doesn't work hard enough." - Christopher Hirst, The Independent

Required reading. Hajdu, who perfectly captured the Dylan/Joan Baez axis of the '60s Village folk scene in "Positively 4th Street," offers his first collection of essays, most published previously in magazines. One that wasn't, however, is an eye-opener on Billy Eckstine. Also enjoyable is Hajdu on Elmer Fudd and his essay "Three Women in Pop: Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Lucinda Williams." - Billy Heller, New York Post

In this collection of essays from a variety of sources, including the New Republic, Hajdu uses his discerning eye to highlight controversial junctures in popular taste. Pieces on music and comic book artists are heavy on background and context and touch on issues of race, aging, authenticity, and technology. Hajdu explores the life of little-known musician Billy Eckstine and includes essays on Elvis Costello, Sting, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, and Alan Lomax. Verdict: This collection from a popular nonfiction writer is recommended for fans and students of music and pop culture writing. - Lani Smith, Library Journal

In this rollicking collection of mostly previously published essays, Hadju (The Ten-Cent Plague; Positively 4th Street) combines the cutting candor of Lester Bangs and the measured and judicious cultural learning of Lionel Trilling as he takes aim at subjects ranging widely from jazz, rock and country music and cartoon characters like Elmer Fudd to broader cultural topics such as blogging, MySpace, and remixing. Hadju writes affectionately about the old Warner Brothers cartoons, recalling the respite they provided from the tumult of the 1960s, every night before dinner. In another essay, he uses the release of Joni Mitchell's album, Shine, as an entrée into a moving retrospective of her music and a bit of mourning over her recent absence from the music scene. In a superb comparison of the music of Lucinda Williams, Taylor Swift, and Beyoncé, he captures Williams as a woman rare among pop stars, possessing unfeathered intelligence, untheatrical carnality, and uncompromising humanity. Hadju's opening essay on jazz great Billy Eckstine is alone worth the price of admission, a poignant portrait of a brilliant musician whose star might have risen even higher had he been born in a different era. Hadju's essays never fail to amuse, please and provoke. (Oct.) - Web Pick of the Week, 9/21/09, Publisher's Weekly

"Hajdu (Journalism/Columbia Univ.; The Ten Cent-Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, 2008) returns with a graceful collection of essays, most previously published, on a variety of topics &151; jazz mostly, but also Elmer Fudd, Elvis and others. The author writes with enormous confidence and competence in these pieces, most of which appeared in the New Republic, where he is a music critic. His encyclopedic knowledge of jazz history and musicians never reduces the prose to pedantry, and he is generally compassionate — though occasionally his criticisms are sharp. In Ken Burns's documentary on jazz, for example, Hajdu detects "subtle hints of racism and anti-Semitism," and he feels the music of Philip Glass can be "frigid." Hajdu is harsh when he needs to be — he declares that there are "four thousand holes" in a recent biography of John Lennon — and is often wry and amusing (see his quotation of Monica Lewinsky's note to President Clinton thanking him for Leaves of Grass). On the whole, the author is an able instructor whose vast knowledge inspires rather than intimidates. He moves easily from essays on celebrities everyone knows (Paul McCartney, Wynton Marsalis) to those known principally to the cognoscenti (Harry Partch, John Zorn). Hajdu includes a lovely essay on the brief life of pianist Michel Petrucciani, whose enormous talent was complemented by his capacious sexual appetite and shortened by bone disease. Among those earning the author's high praise are Susannah McCorkle, Billy Eckstein, Ray Charles and Mos Def. Those stung include Sting, Bobby Darin and Starbucks (whose CDs Hajdu equates with "state-sponsored music"). Occasionally he even chides himself, noting, for example, that as a young man he did not adequately appreciate the cartoons of Jules Feiffer. Hajdu's lengthy piece on Marsalis is a revelation.

"A gift for readers who enjoy erudition seasoned with élan." - Kirkus Reviews

Take a look at the biographical blurb and accompanying author photo on the back cover of David Hajdu's latest book, Heroes and Villains, and you'll discover that not only is Hajdu a professor, but he looks like one. Smiling wryly behind frameless spectacles, the 54-year-old prof (and music critic for the New Republic) folds his arms across the front of his grey, long-sleeve, button-down sportshirt while his short, neat coif blows in the wind.

Yes, Hajdu looks like an unassuming, mild-mannered academic. That, however, is not how he writes. Truth is, the professor is a very tough audience, a master of the cutting sarcastic remark, and a man of unyielding standards. (He really rips apart both Starbucks and late-life Joni Mitchell.) Although, for the most part, the writing in Heroes and Villains — like that of Hadju's previous books Lush Life, Positively 4th Street, and The Ten-Cent Plague — is generous with its criticism.

Whether covering jazz, '60s folk, comic books, Beyoncé, or Elmer Fudd, the prof never pulls a punch, but he also demonstrates a deep love and near-encyclopedic understanding of his material. Perhaps the most lovely (and least known) subject though in Hadju's book is Billy Eckstine, a black jazz singer who equaled Frank Sinatra's star power in the late 1940s before being undone and forgotten by a racist entertainment industry. - S. Pajot, Miami New Times

Even when his subjects are of little to no interest to me, it is clear that David Hajdu is an excellent critic of popular culture. The guy gets a lifetime pass from me for providing the definitive history of the witch hunt against comics in The Ten-Cent Plague, but his latest is nothing to scoff at, either, even if it's a collection of previously published pieces.

But what pieces! Heroes and Villains: Essays on Music, Movies, Comics, and Culture comes complete with nearly 40 articles, most of them culled from the pages of The New Republic. Among its four subtitular subjects, the two holding most appeal to me — movies and comics — actually get an awfully short shrift, but hey, you win some, you lose some.

In the war of words, Hajdu wins. His essays are always — not often, but always — insightful, and penned with a verve that makes critical review transcend mere opinion and lifts it to a realm that approaches some sort of poetry. He may be the only guy who can open a piece on Ghost World's Daniel Clowes by talking about Norah Jones, and have it actually make perfect sense.

Among these pages, MySpace is "a sexual mindfield," while comics are cast as "the rock 'n' roll of literature." Kanye West is "good, though not as good as he thinks. (No one is as good at anything as West believes he is at everything.)" The must-read is a savage skewering of Starbucks for the CDs they sell, calling them "conceived, produced, and marketed with such authoritarian rigor and with such a narrow conception of their listeners' good that they represent nothing less than the return of state-sponsored music."

Other highlights include a look at the musical maturation of Elvis Costello, a tribute to the genius of Will Eisner, and the consideration of Elmer Fudd's sexuality. Any of these alone are nearly worth the purchase. - Rod Lott, Bookgasm

David Hajdu is the music critic for The New Republic and the author of three well received books: Lush Life, (1997) a book about the great jazz composer Billy Strayhorn, Positively 4th Street, (2002) which examines the rise of folk music at the end of the 50s by focusing on the artistic lives, loves, and music of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, her sister Mimi, and Robert Fariña. Hajudu's most recent book before this essay collection was a study of the rise and fall of comic books called The Ten-Cent Plague(2008).

Clearly, Hajdu is on a publishing roll and able to write on a variety of popular culture topics. The essays collected in Heroes and Villains: Essays on Music, Movies, Comics, and Culture come from a wide range of publications: Atlantic Monthly, Los Angles Times Book Review, New York Review of Books and Mother Jones. They show Hajdu as a scholar (he currently teaches journalism at Columbia University) and journalist who is interested in making sense out of the current cacophony in contemporary music and the myriad forces — both personal and technological — that shape the artistic production and public consumption of music. The essay on My Space is a good example of Hadju being able to explain and show how the contemporary phenomena of My Space is actually responsible for a certain conformity of taste and that it is not the great liberator of human musical creativity it is reported or hoped to be.

Hajdu's 2003 piece simply called "Wynton Marsalis" is a brilliant analysis about Marsalis' place in jazz history. The essay uses the rise and fall of Marsalis' standing in popular culture as a metaphor for the rise and decline of jazz in popular culture and tells how his brother Branford represents the progressive/evolutionary side of jazz. Wynton is the classicist, brother Branford the bold brassy new wave jazz creator.

It's a clever piece of writing and weaves into the text catching a chance performance of Wynton in a small club on a vacant weeknight in August in New York, the sound of a cell phone going off, and then Marsalis' ability to play each note of the cell phone ring. It's a clever introduction to what becomes a reflective trenchant meditation on jazz and Wynton Marsalis.

Hajdu's affectionate recollections of watching Elmer Fudd cartoons on Saturday afternoons is another example of Hajdu's clear writing style and his ability to write insightful portraits. The Elmer Fudd essay is a smart piece of character analysis. Fudd is "a grown man, old enough to have gone completely bald, Elmer J. Fudd is an oversized newborn, proportionally and psychologically."

Hajdu's is also an historian of popular culture. For example, "Billy Eckstine: The Man Who was Too Hot" shows us Hajud's ability to enter sympathetically into a past era to frame the success and almost stardom of a now mostly forgotten Eckstine. Hajud resurrects Eckstine's style and singing ability and laments how the sexual mores of the ‘50s and unspoken racism of the time prevented Eckstine from achieving stardom.

This collection also includes essays that critically examine books about famous pop music stars such as Sammy Davis Jr. and John Lennon. In these essays Hajdu is his most critical. His scathing essay on Sting's medieval inspired CD is amusing in its dressing down of Sting's preposterous and pretentious singing style and choice of music.

Part of what makes Hajdu such a good music critic and clever pop culture observer is his ability to see beyond the obvious. Here, for example, is Hajdu on Sammy Davis Jr. "We don't remember Davis for who he was or what he did when he mattered most as much as for the wicked joke he let himself become."

Hajdu has a keen sense of the social significance of pop culture artists and he shows how they often reflect and create the social climate of the day. Hajdu's deep appreciation and knowledge of music, especially jazz, however, does not prevent him from administering 'tough love.'

In "The Great Men of Jazz", Hajdu chastises Ken Burns' CD and text for ignoring huge swaths of Jazz history. He admonishes Philip Norman's book John Lennon: The Life for his ham-fisted treatment of Lennon's lyrics and his "repetitious… bloodless prose."

Throughout, Hajdu writes in a clear, straightforward style and possesses a sympathetic feel for the lives and music of pop music performers, and this in turn allows him to get past the surface of their lives. Anita O'Day and Bobby Darrin, for example, reshaped themselves and used their talent to climb onward and upward to the top of their musical fields, he writes. The result, however, as in Bobby Darrin's case, was tragic; he lost his way or identity by recalibrating his musical identity over and over again to try and maintain popular culture success. O'Day's personal life turned out to be a disaster.

Hajdu's literary voice is thoughtful, urbane, and cosmopolitan in a very New York City sort of way. His pop culture gaze seldom looks beyond the US except for the essays on the two former Beatles, Paul McCartney and John Lennon, and his tribute essay to the French-Italian jazz pianist Michel Petrucciani; the latter mainly because he both succeeded and ended his career in New York.

Jazz, as Hajdu recognizes, is no longer America's music but has become a world musical form absorbing the sounds and flavors from diverse cultures from around the globe. Alas, I wish some of the essays reflected this reality. This is not so much a flaw as a question of focus. - Carmelo Militano, PopMatters

Though he's widely known for The Ten Cent Plague, his 2008 book on the U.S. government's 1950s war on comics, David Hajdu has long been a music critic for The New Republic. Heroes and Villains is primarily focused on the musical end of things, but as its full title notes, contains explorations into music, movies, comics, and the broader cultural landscape as well.

Hajdu (pronounced Hay-due, for those keeping score) knows his stuff, whether he's extrapolating on The White Stripes, Paul McCartney, or Taylor Swift, he offers an incisive, thoughtful commentary on the material and the artists behind it. Especially refreshing is that Hajdu is mindful that there's a musical world beyond rock 'n' roll, and some of the book's most winning moments come when the author takes on the wide world of jazz. While the pieces that stick primarily to one artist are generally more successful than those examining broader cultural trends, the collection's finest moment comes via Hajdu's evisceration of the music sold at Starbucks. Readers disdainful of greatest hits compilations and over-priced coffee are sure to love it, as Hajdu details the way such "essential" packages short change independent musical discovery.

Guys like David Hajdu are a rare breed anymore, as criticism — truly thoughtful criticism, not just a "thumbs up or thumbs down" review — further erodes from the journalistic and cultural landscape; fittingly, Heroes and Villains was recently named as a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award. He's a kindred spirit to writers like The New Yorker's Sascha Frere-Jones and Anthony Lane or The New York Times' A.O. Scott. (It should be noted that of those three, only Frere-Jones covers music; Lane and Scott are film critics). And while Hajdu get a little dry at times— how about having a little humor about it all, eh?— it's good to know there's still a space for scribes of that nature. - Aaron Passman, Under the Radar

Reading David Hajdu's Heroes and Villains is enough to make any rational music critic hang up their keyboard and walk away. His work for The New Republic is a true joy to read. Hajdu writes not clinically, but with a matter-of-fact tone that gets to the heart of the subject about which he’s writing. While he avoids overly flowery prose, Hajdu's words evoke a simple lyrical charm.

Hajdu's operating voice lends authority and credence to all sides of of a story. He frequently plays the devil's advocate, as in his profile of jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. In this piece, he speaks both to Marsalis' positive uplift of jazz with his work as part of Jazz at Lincoln Center, as well as his contribution to to the genre’s stagnation.

Even his evisceration of "Sting the Lutenist," wherein he declares the former Gordon Sumner to come off as "haughty and strident," he still manages to allow that "the prospect of Sting attempting to perform such quiet, delicate music was tantalizing."

As an added bonus, by collecting pieces written over a period of years means that the reader can glean Hajdu's overarching themes. In this case, it is his focus on rock as youth, regardless of the age of the actual performer. Even though Chuck Berry’s been playing his songs for well over 50 years at this point, his songs still serve "anathema to everything that Johnny Mercer and his milieu represented — refinement, maturity, professionalism."

Hajdu’s trumpeting of the "unsung," such as vocalist Billy Eckstine, is truly what drives this book, however. When speaking of jazz, or any other genre, and the tendency to focus on the "great man" theory of venerating the big names, while ignoring those artists that might have any sort of commercial success, Hajdu's on the offensive. He points out the fact that Ken Burns ignores Latin jazz pioneers like Xavier Cugat, or that "essential" compilations cut out the performances that might give a view of an artist that's not the party line. Essentially, anything that might make a performer seem to be something exotic is taboo, and Hajdu makes sure that there is voice given to them. - Rock Star Journaliste